- Why did you choose to research Congo and Belgian colonial history?

During my history studies at the University of Ghent, I was growing a bit tired with Belgian and European history. To escape that, I took a number of optional courses on African history and wrote my thesis on Congo. When I was given the opportunity to pursue a PhD, I chose Congo Free State (when Congo was the private property of King Leopold II of Belgium, between 1885 and 1908) as my subject. I did research on taxes and customs duties. I know it sounds boring, but it's not. I wanted to examine from a practical point of view how the Free State took shape. Where did the money come from? From that question it’s just a matter of time before you get at the rubber industry and forced labour. And that's how I ended up in the Heritage Library. There's a lot of source material here that’s not available online, but it's still very relevant.

- Like what?

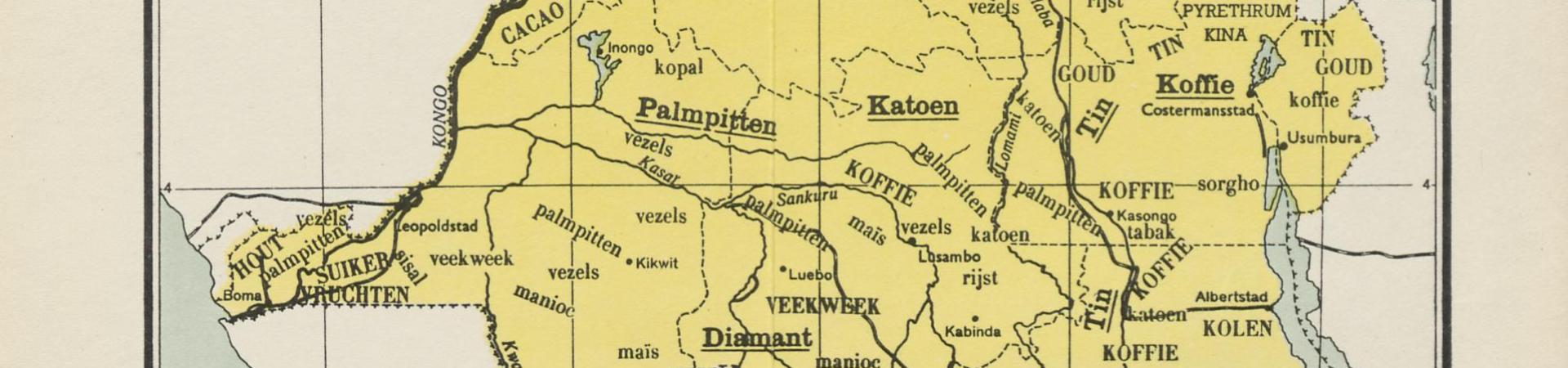

I first came here to consult Le mouvement géographique (1884-1922), a magazine with travel reports of Belgians in Congo that is very useful for a better understanding of the local context. Very important for my doctorate was the Ambtelijk blad, the official journal of Belgian Congo (1908-1959), which allowed me to map out budgets and tax laws. Unique in your collection is the Caoutchouc series by Grisar & Co (1899-1913), an auction house in rubber. It shows day by day who bought and sold rubber. As far as I know the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library is the only library that preserves it. If you take the time to map it all it can help you understand who profited from the looting regime of Leopold II.

- I always thought our sovereign had become rich from the start by installing a predatory regime?

That was the initial idea, but that’s not how it worked out. Leopold paid for the occupation out of his own pocket. Congo Free State initially did not have much to offer Western industry. There was only trade in ivory, but that was a luxury product, not something that you could build wealth upon. Fortunately for the king, the price of rubber soared at the end of the nineteenth century. Suddenly everyone needed inflatable tyres for bicycles and cars. Rubber saved his colonial project. But that colonial success of course caused a huge tragedy because the coloniser installed a reign of terror that forced the Congolese population to produce rubber.

- Was there also a critical voice in Belgium against the atrocities of the colonial regime?

Yes, but actually Leopold's opponents were also looking at Congo with a colonial look. They wanted to free the "poor Congolese" and save them from Leopold II's colonial plunder regime. They ignored the crucial role of the population in the resistance to Leopold's reign of terror in their many publications.

- Did Leopold II encounter much opposition from the local population?

Absolutely, but that's not the whole story. The population did more than play victim or resist. Anyone who wants to know all about it should read the book Being colonized (2010) by the Belgian researcher Jan Vansina. That is also in your collection. What is groundbreaking is that Vansina writes from the perspective of the Central African population and shows that 'the colonised' did not form a homogeneous group and also played an active role in the colonial history of Africa. Local leaders, for example, cooperated in the colonisation, whether or not out of fear of reprisals. They governed their people in the name of the coloniser and let them supply ivory and rubber. As long as they did what the colonizer asked, they remained fairly independent. If they did not listen, the punitive expeditions came.

- The average Belgian knows little about Congo's pre-colonial history. Why is this?

Until recently, the history of Congo only began in most school textbooks when Leopold II appropriated the area around the Congo Basin. The fact that people lived in Congo with their own history was ignored. This did not fit in with the colonial story where the white pioneers discovered Africa and brought civilization to its primitive inhabitants. This one-sided and stereotypical image is also abundant in your Congo collection. It therefore requires some expertise to frame all publications correctly. Take the book A journal of a tour in the Congo Free State by Marcus Dorman. This is a travel report – presumably financed by Leopold II – which insinuates, among other things, that the severed hands were the result of illness or attacks by wild beasts. Fortunately, we know better today, but it is a good example of propagandistic historiography. The same can be said of Our Colony, an overview written in the 1930s by the then director of the Colonial College in Antwerp. Until the 1950s, it was reprinted in various ways, including all possible racist descriptions. A chapter entitled "The intellectual abilities of the blacks" now sounds an alarm bell because it is so stereotypical, but many colonial sources use terminology and imagery that is much more muddled. This still works today in our collective memory.

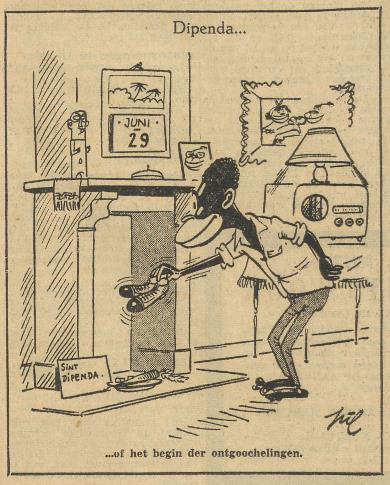

- On the eve of the independence of Congo, the newspaper De Standaard published a cartoon that we consider racist today. It’s very confronting to find that even a mainstream Flemish newspaper allowed this.

The cartoon is a fine example of colonial imagery. Throughout the colonial period, the Congolese were depicted as a simple and primitive creature. Without the good care of the civilised white people, the Congolese would never get any further. That image has been rammed into our minds for decades through school books, newspapers, television, films, monuments, etc. Today that view of Africa and Africans lives on, just like our own white sense of superiority. A way of looking at the world that has been repeated for a century does not just disappear. A compelling example is the speculaas portrait made of president Obama, which depicts the black president in almost as racist stereotypes – exaggeratedly thick lips and nose – as the cartoon in De Standaard from 1960. (A baker created a representation of the American President Barack Obama in speculaas, for the occasion of Obama's visit to Belgium in 2014.)

The cartoon is a fine example of colonial imagery. Throughout the colonial period, the Congolese were depicted as a simple and primitive creature. Without the good care of the civilised white people, the Congolese would never get any further. That image has been rammed into our minds for decades through school books, newspapers, television, films, monuments, etc. Today that view of Africa and Africans lives on, just like our own white sense of superiority. A way of looking at the world that has been repeated for a century does not just disappear. A compelling example is the speculaas portrait made of president Obama, which depicts the black president in almost as racist stereotypes – exaggeratedly thick lips and nose – as the cartoon in De Standaard from 1960. (A baker created a representation of the American President Barack Obama in speculaas, for the occasion of Obama's visit to Belgium in 2014.)

- What can the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library do to adjust this image?

Our colonial past is omnipresent in Antwerp, with the Colonial College, the Antwerp Zoo, the Tropical Institute, Umicore (the succesor to the mining company Union Minière), the White Fathers Missionaries of Africa, and therefore also your collection. Antwerp is a very visibly colonial city! For this reason alone, we have to work with this past to tell a polyphonic story. The Heritage Library could show how this collection started and grew, how the books repeated the same stereotypical stories for decades. With all this material you can create an exhibition or put together a nice educational package for school children. But I repeat: the collection is very "colonial" and "white". Don't burn those books! But put them in the right context. What do you do if you have a picture of an African in tribal costume next to a colonial in an immaculate white suit? Without further explanation, it reaffirms the stereotypes.

- Has the history of Congo been written in its entirety?

A great deal of academic research has already been done, but this usually focuses on the figure of Leopold II or on the road to independence. There is still a lot we don't know. Heaps of archive material have never been used because there is simply too much. Belgium is known for its extensive administration and bureaucracy, and that was no different in the past. An additional problem is that academic research doesn’t find its way to the general public. Many academics stay in their ivory tower. It’s a good thing there is more attention for Congo this year. In Antwerp the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library will organize a series of Nottebohm lectures and the MAS will show an exhibition 100 x Congo on the image of Africans through time. In the Middelheim Museum there is the Congoville exhibition and, together with the University of Antwerp, they organise a symposium ZOOMING IN / ZOOMING OUT. This museum also asked us to do a study on colonial monuments in Antwerp. What is clearly noticeable is that symbolic data are often the reason to explore a theme. So let's make sure that after the sixtieth anniversary of independence in 2020, Congo continues to have our attention.

![Overview of the lots of rubber that were sold by the auction house Grisar and Co. on 26 June 1903 by order of the trading house Bunge & Cie [EHC 741828]](/sites/ehc/files/styles/large/public/caoutchouc_741828.jpg?itok=EHlwA5YT)