In 1656, while in exile in Antwerp during the English Civil War, the English noblewoman Margaret Cavendish, Marchioness of Newcastle (1623–1673), donated a book to the Antwerp city library, now categorized by the classmark C 1039:ex.1.

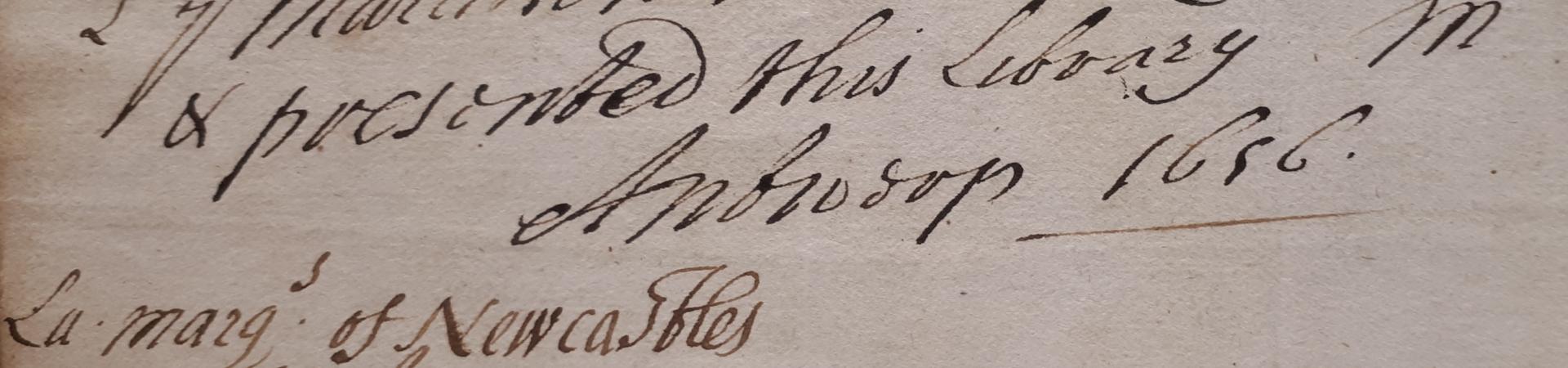

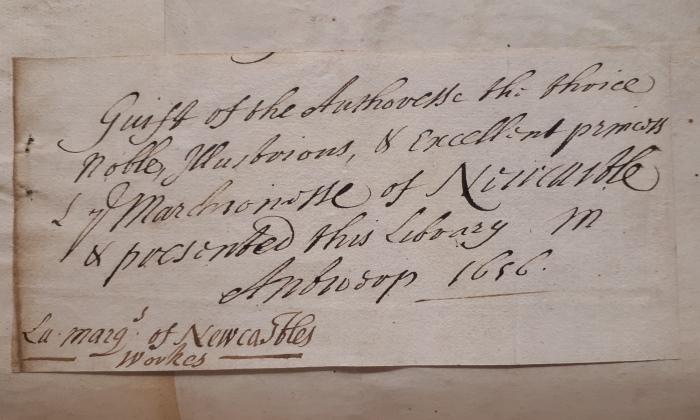

The slip of paper, most likely originally attached with a straight pin (based on the small black holes left in the edge of the paper) reads: “Guift of the Authoresse the thrice Noble, Illustrious, & Excellent princess the Marchionesse of Newcastle & presented this Library in Antwerp 1656.” Another hand, in a lighter ink, writes underneath, “La[dy] Mar[chioness] of Newcastles Workes.”

By the time she donated this book to “this Library in Antwerp,” Margaret Cavendish, born Margaret Lucas, had been living in Antwerp for eight years. After a somewhat sheltered upbringing in the comfort of her coddling family, she had gone on to serve as a maid-in-waiting for Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I of England. While serving the Queen, Margaret lived with her in Merton College, Oxford, for a year, fled with her to Bath, and then eventually followed her to Paris, where Margaret met her future husband William Cavendish. After their marriage, the Cavendishes moved to Antwerp, where they took up residence in the Rubens house for twelve years while waiting for the eventual Restoration of the monarchy in England.

Cavendish’s biographer Katie Whitaker has detailed the various ways that Margaret and William integrated themselves into local society while in Antwerp: the local Antwerp merchant Francis Topp eventually would marry Cavendish’s maid and return with the family to England; she frequently visited the prominent Duarte family and letters between them survive; and she corresponded with Constantijn Huygens, who facilitated the submission of books to the Leiden University Library on her behalf, and who engaged in epistolary debates with her about scientific experiments long after she and her husband had returned to England. Huygens would also eventually donate another book on her behalf to the Leiden University, and Cavendish went out of her way to donate her books to every college in Cambridge and Oxford Universities both before and after the Restoration, in an attempt to make her works survive.

It is perhaps noteworthy that Francis Topp also inscribes the back of an engraving inserted before The World’s Olio in the Conscience Library copy with the classmark C 1039:ex.1. The inscription, which reads, “Francis Toppe his Booke 1655. | being ye Guift of her Excellency:” suggests that it may have been given to Topp first before the book was donated to the central library, by Topp or by herself.

It is no surprise that Cavendish would extend her bibliographical generosity to the city that hosted her from the ages of 25–37, the city where she spent a large amount of her adult life and into which she integrated herself so thoroughly. There are, however, some striking things about the text itself once one moves past the slip noting the donation; this article outlines those unique features, and gestures to some avenues for further research.

First, the donation slip reads “La[dy] Mar[chioness] of Newcastles Workes” because the text that follows is a Sammelband, a collection of books often found together that have been bound together into one comprehensive collection. The single volume contains four books, all save one that she had published by 1656: the 1653 collection Poems and Fancies; the 1655 natural philosophical treatise Philosophical and Physical Opinions; the 1655 essay collection The World’s Olio; and the 1656 short story collection Nature’s Pictures. By binding them together, as I am arguing elsewhere, she links very different kinds of writing together: her stories rub shoulders with her essays, and natural philosophical speculation appears between the same covers (and immediately after) her poems. Her Poems and Philosophical and Physical Opinions are also bound together in a copy of this text held at the British Library, shelfmark C.39.h.27. Even more remarkably, this particular collection of texts appears in three other places in Europe: one in the Bibliothèque Mazarine, one (donated by Huygens) in the Leiden University Library, and a second one located in the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library, classmark C 1039:ex.1, also bearing a note marking it as a donation of the author (“Ex Dono Scriptris”) in the front pages. (For ease of further reference, in what follows I shall refer to C 1039:ex.1 as “Copy 1” and C 1039:ex.2 as “Copy 2”.)

Second, each of the two volumes is riddled with handwritten notes, some of which are in Cavendish’s very distinctive hand. This is not all that unusual: as has been shown elsewhere, Cavendish regularly made, or had made, systematic manuscript or hand-written corrections in her books, particularly before donating them to distinguished friends or libraries. However, the fact that the Conscience Library has two copies makes it easier to compare corrections across copies, and unlike some of her other annotation patterns, the handwriting and other copy-specific features varies across the two volumes. What the Conscience Library copies show us is significant and sustained interaction by Cavendish with her books after they had been printed, but of a radically different kind than that described by Fitzmaurice or by myself, having examined only UK and North American copies.

Below I describe three noteworthy features of the Conscience Library’s two Sammelbände, as well as a brief explanation of what makes those features noteworthy:

1) The first edition of Cavendish’s Poems and Fancies contains, in a very few copies given to elite libraries, a dedicatory poem written by her husband; I have found this poem in only 5 of 25 copies of the 1653 Poems that I have examined, including one donated by her to the Cambridge University Library and one donated by her to the Bodleian Library in Oxford. In the Conscience Library, Copy 1 has this rare first edition of a dedicatory poem, while Copy 2 does not. This signals, perhaps, that Copy 1 was more distinguished in her mind; only copies going to major libraries received this prefatory poem.

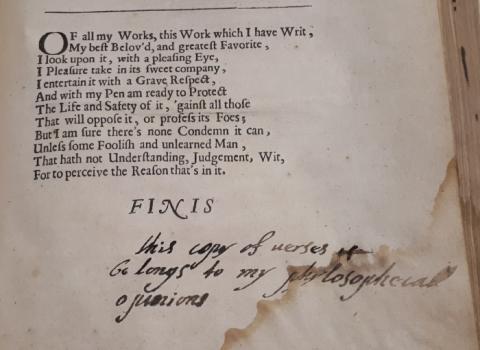

2) The last page of The World’s Olio has a poem naming the current work as “My best Belov’d, and greatest Favorite,” seemingly referring to the text in which it was printed. In Copy 2, however, a note in Cavendish’s own hand reads, “this copy of uerses belongs to my phylosophicall opinions” – that is, the poem was meant to be printed at the end of her 1655 Philosophical and Physical Opinions, not at the end of her 1655 World’s Olio. A similar note appears in a copy of this text held at the British Library, shelfmark 841.m.22. This note provides a key detail of the two volumes’ printing history: that the poem could be attached to the “wrong” text suggests that the printer may have been printing both texts simultaneously.

3) Copy 1 does not have the note about the misplaced verse that can be found in Copy 2’s World’s Olio, nor does it have a note on p. 213 of that text. Further, in both copies the last text, Nature’s Pictures, contains hand corrections on over 40 pages each – some in her hand, and some in two different hands not her own. Some changes appear in both copies, while some changes appear only in one copy.

This final point is perhaps the most important, because unlike the systematic manuscript changes found in copies being shipped to Oxford, and made by someone else on her behalf, the variant hand-corrections in the two copies surviving in the Conscience Library suggests that the two volumes, and the eight books they contain in total, served as “living” texts before being enshrined in the public library of Antwerp for safe-keeping. The numerous hand changes show, that is, a woman reading her own work in print, and making notes of things she wanted fixed as she went along. They started their life, that is, as active texts, whose complicated sets of hand corrections not only show other readers responding to her works, but show the author herself both revisiting her own work, and making notes for future revisions. It shows a woman reading and responding to her work in different phases, noticing different things each time, and in different copies.

In short, the two Cavendish Sammelbände held at the Conscience Library would afford much further and more detailed study, particularly by with attention to hand corrections across the two volumes. Such a study, of Cavendish’s detailed reading and correcting of her own writing, might help shine further light on her time in Antwerp, which she evidently spent not just displaying herself in carriages and attending salons, but doing one of the things she loved best: honing her writing craft in preparation of another fifteen years of publishing.

Liza Blake

University of Toronto

liza.blake@utoronto.ca

Liza Blake is Assistant Professor in the English Department at the University of Toronto. She is currently finishing a monograph entitled Early Modern Literary Physics, which examines the connections among literature, science, and philosophy in the English Renaissance, and is developing a monograph on the atom poems of Margaret Cavendish. Her trip to Antwerp was funded by a SSHRC Insight Development Grant for this second project, Choose Your Own Poems and Fancies: A Digital Rearrangeable Edition of Margaret Cavendish’s Atom Poems.

Further reading

- Akkerman, N., and Marguérite Corporaal, “Mad Science Beyond Flattery: The Correspondence of Margaret Cavendish and Constantijn Huygens,” Early Modern Literary Studies Special Issue 14 (May, 2004): 2.1-21, http://purl.oclc.org/emls/si-14/akkecorp.html.

- Blake, L., “Pounced Corrections in Oxford Copies of Cavendish’s Philosophical and Physical Opinions; or, Margaret Cavendish’s Glitter Pen,” New College Notes 10 (2018), no. 6: 1-11.

- Blake, L., “Textual and Editorial Introduction,” in: Margaret Cavendish’s Poems and Fancies: A Digital Critical Edition, ed. Liza Blake (website published May 2019), http://library2.utm.utoronto.ca/poemsandfancies/, section I.

- Cavendish, M., Nature’s Pictures (London, 1656), 368-391.

- Fitzmaurice, J., “Margaret Cavendish on Her Own Writing: Evidence from Revision and Handmade Correction,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 85 (1991): 297-307.

- Huwel, R., “Een gift aan de Stadsbibliotheek in 1656,” Antwerpen 30 (1984), 52-56.

- Keblusek, M. “Literary patronage and book culture in the Antwerp period,” in: Royalist Refugees: William and Margaret Cavendish in the Rubens House, 1648-1660, ed. Ben Van Beneden and Nora de Poorter (Antwerp: Rubenshuis and Rubenianum, 2006), 105-109.

- Letters and Poems in honour of the incomparable Princess, Margaret Dutchess of Newcastle (London: In the Savoy, printed by Thomas Newcombe, 1676), 1-2.

- Van Impe, S., “The Special Collections of the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library (Antwerp), result of a long history,” Archief- en Bibliotheekwezen in België 84 (2013) 1-4, 129-141, esp. 132.

- Whitaker, K., Mad Madge: The Extraordinary Life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, the First Woman to Live by Her Pen (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 104-248, esp. 104-132.