Lonely Planet, Rough Guide, Capitool or Michelin – it is just a selection of a seemingly endless supply of travel guides available on the market today. These guidebooks come in different shapes and sizes: from concise, flashy books, that zero in on the most authentic and unexplored hideaways to the more stylish and elaborate versions, aiming for comprehensiveness. They all offer information for devotees of art and culture, but also comprise more specialized sections for hikers and cyclers, foodies and fashionista’s, and numerous other groups. However, this was not always the case. Modern travel guides are the result of a long historical evolution, which started centuries ago. The (digital) collection of travel guides of the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library casts a unique light on the slow genesis of the genre.

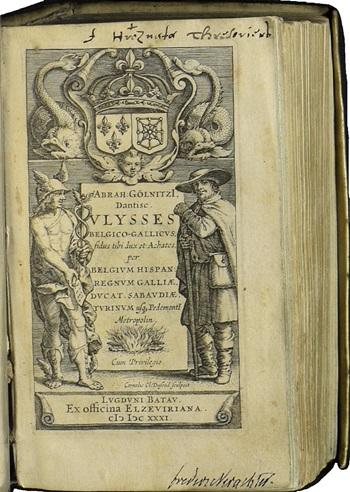

A true classic is, for example, the Ulysses Belgico-Gallicus by Abraham Gölnitz (Goelnitzius). After the original, Latin version published by Elzevier in Leyden in 1631, a long list of translations and adaptations came from the presses. Strictly speaking, Gölnitz’ guide is a travel diary through France and parts of Italy, the Low Countries and the Holy Roman Empire. Yet the book offered so much practical information about roads, inns, food, and other everyday concerns along the way, that it was also often used as a travel guide. Gölnitz even added a model contract for the Veturino, so that unwary northerners would not be ripped off by cunning – and especially greedy – Italian coachmen. The book also gave lots of information about sights and attractions en route, including descriptions of dozens of cities in minute detail. For example, in the French translation of Louis Coulon, Antwerp is described as a gem – “Als Vlaanderen de ring is, is Antwerpen de diamant.” [“If Flanders is the ring, Antwerp is the diamond.”] – with particular attention to the colossal Our-Lady-Cathedral, the impregnable citadel, the stunning Jesuit Church and – the eighth Wonder of the World – the Plantin Press. Together with a wide range of other travel guides, Gölnitz lay the foundations of the classical Grand Tour; a long, educational trip through France and Italy, which was very popular amongst noblemen and wealthy citizens.

A true classic is, for example, the Ulysses Belgico-Gallicus by Abraham Gölnitz (Goelnitzius). After the original, Latin version published by Elzevier in Leyden in 1631, a long list of translations and adaptations came from the presses. Strictly speaking, Gölnitz’ guide is a travel diary through France and parts of Italy, the Low Countries and the Holy Roman Empire. Yet the book offered so much practical information about roads, inns, food, and other everyday concerns along the way, that it was also often used as a travel guide. Gölnitz even added a model contract for the Veturino, so that unwary northerners would not be ripped off by cunning – and especially greedy – Italian coachmen. The book also gave lots of information about sights and attractions en route, including descriptions of dozens of cities in minute detail. For example, in the French translation of Louis Coulon, Antwerp is described as a gem – “Als Vlaanderen de ring is, is Antwerpen de diamant.” [“If Flanders is the ring, Antwerp is the diamond.”] – with particular attention to the colossal Our-Lady-Cathedral, the impregnable citadel, the stunning Jesuit Church and – the eighth Wonder of the World – the Plantin Press. Together with a wide range of other travel guides, Gölnitz lay the foundations of the classical Grand Tour; a long, educational trip through France and Italy, which was very popular amongst noblemen and wealthy citizens.

Over half a century later, Jan ten Hoorn – an ambitious Amsterdam printer – published the Reis-boek door de Vereenigde Nederlandsche Proviciën en der zelver aangrenzende landschappen en koningrijken. Ten Hoorn’s travel guide was an instant hit. After the original edition of 1689 several reprints followed. The success was due to the ground-breaking structure of the book. First and foremost, Ten Hoorn focussed on the Low Countries – especially the Northern Netherlands, but also the Southern part. Obviously, he also described France, Italy, Switzerland, the Holy Roman Empire, the Iberian Peninsula and even the barren North in order to suit travellers venturing on a classical Grand Tour through Europe, but the lion’s share of the text zeroes in on domestic trips through Holland, Zeeland, Friesland, Groningen or Guelders or – a little more adventurous – over the border to Flanders, Brabant or the Prince-Bishopric of Liège. The information was highly useful for Dutch senior officials, regents, and businessmen, but also for preachers, lawyers, and other members of middle groups, who increasingly set out on short plaisierreijsjes [pleasure trips] in their own country or beyond the border. Secondly, the practical sections in Ten Hoorn’s travel guide were innovative. Apart from a description of the cities and sights en route, the book included detailed information on modes of transport – diligences, coaches, tow-barges, and packet-boats – including departure times and prices. Inns, hotels and other accommodations were also listed. In Brussels, the offer varied from very expensive (including the Keizerin [the Empress] and the Rooden Arend [the Red Eagle]) to – more or less – affordable (De Spaansche Kroon [The Spanish Crown] and In den Graeve van Egmond [The Count of Egmond]). In addition, ten Hoorn’s guidebook also contained a medicijn-boek [medicine book] – with remedies against rheumatism, seasickness and ‘coach sickness’, colic and other ailments – an overview of foreign weights and measures, a perpetual almanac, some prayers and spiritual songs, and various other practical instructions.

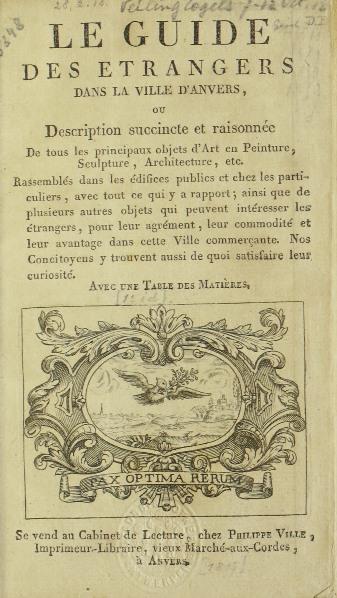

Until the nineteenth century, guidebooks rarely if ever came from Antwerp presses Le Guide des Etrangers dans la ville d'Anvers (Antwerp 1817) is the proverbial exception to the rule. This thumbed travel guide is also special in other respects. First and foremost, it is an example of a new subgenre. After all, city guides were initially scarce. For a long time, countries – or at least regions – were the favourite scale of travel guides, chorographies, and other geographical literature. It was not until the middle of the eighteenth century that specialised guidebooks for Rome, Paris or London appeared on the market. Antwerp made it to this list thanks to its baroque art treasures, which attracted numerous British, French, German and Dutch connoisseurs. The subtitle of Le Guide shows that these étrangers were mainly interested in les principaux objets d'art et de peinture, sculpture et architecture, of which the masterpieces of Rubens and Van Dyck in particular had an irresistible appeal. In guides such as Le Guide, would-be connoisseurs were also given tools to assess these chefs-d’oeuvres in correct terminology – in terms of composition, design, colouring, perspective, chiaroscuro and other jargon. Yet, these travellers were less enthusiastic about the city itself. Antwerp was increasingly described as a ravaged and abandoned metropolis: Europe’s Dullsville where time had frozen since the late sixteenth century, when the city had faced its cataclysmic Fall in 1585.

Until the nineteenth century, guidebooks rarely if ever came from Antwerp presses Le Guide des Etrangers dans la ville d'Anvers (Antwerp 1817) is the proverbial exception to the rule. This thumbed travel guide is also special in other respects. First and foremost, it is an example of a new subgenre. After all, city guides were initially scarce. For a long time, countries – or at least regions – were the favourite scale of travel guides, chorographies, and other geographical literature. It was not until the middle of the eighteenth century that specialised guidebooks for Rome, Paris or London appeared on the market. Antwerp made it to this list thanks to its baroque art treasures, which attracted numerous British, French, German and Dutch connoisseurs. The subtitle of Le Guide shows that these étrangers were mainly interested in les principaux objets d'art et de peinture, sculpture et architecture, of which the masterpieces of Rubens and Van Dyck in particular had an irresistible appeal. In guides such as Le Guide, would-be connoisseurs were also given tools to assess these chefs-d’oeuvres in correct terminology – in terms of composition, design, colouring, perspective, chiaroscuro and other jargon. Yet, these travellers were less enthusiastic about the city itself. Antwerp was increasingly described as a ravaged and abandoned metropolis: Europe’s Dullsville where time had frozen since the late sixteenth century, when the city had faced its cataclysmic Fall in 1585.

The idea of faded glory disappeared completely in Belgique et Hollande (Leipzig 1886); a modern travel guide by the German publisher Karl Baedeker. For decades, the "little red book" guaranteed a smooth travel experience. Baedeker not only provided a wealth of practical information about transport modes – in addition to the classic coaches and barges, now also trains, trams, omnibuses and steamships – and accommodation, but also advice about cafés, brasseries and restaurants. Readers also found their way to the local telegraph and post office, to the most elegant boutiques and shops – lace at Diegerick, travellers’ items at Carlier, photographs and paintings at Thirion – to theatre and concert halls, public libraries and baths, and – a novelty – to the local tourism office of Anvers en Avant [Antwerp Forward]. Baedeker also listed the sights: the classics – with the Cathedral of Our Lady, the Town Hall and the Stock Exchange on top of the list – were coupled to a host of new attractions such as the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, the National Bank, the City Park, the jardin zoölogique (zoological garden) and the new docks.

The idea of faded glory disappeared completely in Belgique et Hollande (Leipzig 1886); a modern travel guide by the German publisher Karl Baedeker. For decades, the "little red book" guaranteed a smooth travel experience. Baedeker not only provided a wealth of practical information about transport modes – in addition to the classic coaches and barges, now also trains, trams, omnibuses and steamships – and accommodation, but also advice about cafés, brasseries and restaurants. Readers also found their way to the local telegraph and post office, to the most elegant boutiques and shops – lace at Diegerick, travellers’ items at Carlier, photographs and paintings at Thirion – to theatre and concert halls, public libraries and baths, and – a novelty – to the local tourism office of Anvers en Avant [Antwerp Forward]. Baedeker also listed the sights: the classics – with the Cathedral of Our Lady, the Town Hall and the Stock Exchange on top of the list – were coupled to a host of new attractions such as the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, the National Bank, the City Park, the jardin zoölogique (zoological garden) and the new docks.

Gerrit Verhoeven

UAntwerpen

gerrit.verhoeven@uantwerpen.be