Of Lanseloet and Sanderijn

This newly discovered Lantslot is an edition of the work canonically known as LanseloetvanDenemerken. It forms part of the so-called abele spelen, a set of plays generally considered to be some of the oldest Dutch secular theatre texts. The title is drawn from the earliest surviving version, found in the Van Hulthem codex from the early fifteenth century. However, scholars estimate that the work itself originated in the middle of the fourteenth century.

The play tells of Lanseloet, prince of Denmark, who longs for his mother’s maid Sanderijn, but Sanderijn feels she cannot marry the socially superior prince. Lanseloet’s mother is appalled by her son’s hankerings which, she believes, are purely driven by physical desires. On the condition that Lanseloet renounces the girl, his mother tricks Sanderijn into his room where, through force or deception, Lanseloet rapes her. Distraught, Sanderijn flees the court, the country and the continent. In Africa, she is found by a nobleman who proposes to marry her. In what is surely a highlight of Middle Dutch poetic imagery, Sanderijn responds by describing a beautiful, blossoming tree robbed of a single flower by a passing falcon. The nobleman reassures her: what she has to offer far outweighs what has been taken from her. Back in Denmark, a repentant Lanseloet dies of a broken heart.

Early Modern popularity

Lanseloet is the only abelspel which has survived into the early modern period, being printed multiple times from the late fifteenth century onwards. This enduring popularity may be due to the play’s complexity and nuance. It is neither a tragedy nor a comedy, which sets it apart from the other abelespelen with their straightforward happy endings. Another reason for its success may have been the pragmatic portrayal of love and marriage. This may have resonated with early modern bourgeois audiences who despised unbridled passion.

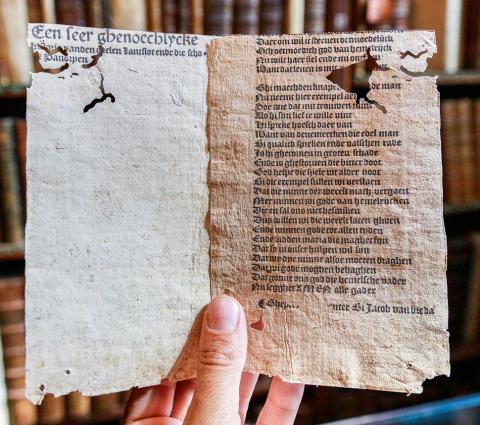

The two earliest known editions of the Lanseloet were printed by Govert van Ghemen in Gouda around 1486-1492. Van Ghemen, or possibly an earlier printer, retitled the work Historie vanden eedelen lansloet ende die scone sandrijn and removed the stage directions, thus creating a text suited for private reading. On the whole, however, these editions are remarkably close to the Van Hulthem-Lanseloet text, even though they are probably not derived from that textual witness. The Gouda-prints seem to be the basis of later prints, which hew closely to them. Unfortunately the only known copy of one of these Ghemen editions was lost in the Second World War, leaving us with a transcription, while only a single fragment survives of the other.

Lantslot in the Conscience Library

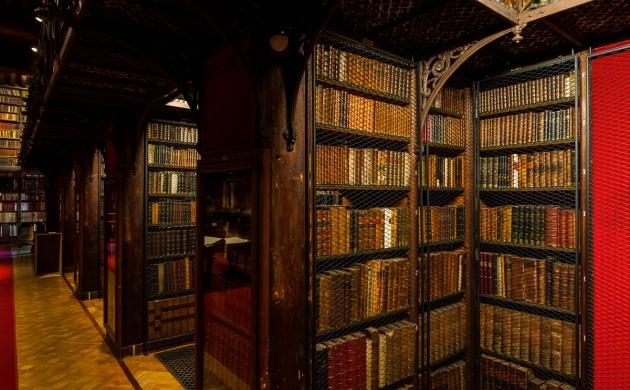

During a restoration campaign in the 1980s, the Stedelijke Boekbinderij removed the Lantslot-leaves discussed here, together with several other fragments of printed and manuscript material, from the binding of two 16th-century Latin books printed in Germany and held by the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library. The library added these fragments to a sizable collection of uncatalogued medieval and early modern ‘membra disiecta’. There they were recently identified by the project team working on Medieval Manuscripts in Flemish Collections, an initiative of the Vlaamse Erfgoedbibliotheken which aims to develop a database containing all medieval manuscripts located in Flanders.

Although only four leaves remain of this Conscience-Lantslot, they provide us with much information. Since both the title page and colophon have survived, we know the exact title and who printed the work: Jacob van Breda. Van Breda was active as a printer between 1485 and 1518 in Deventer, the largest printing centre in the late fifteenth-century Low Countries. Unfortunately, no date is mentioned and neither there is a printer’s device, which would have allowed for a more precise dating. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Conscience-Lantslot is one of the earliest surviving editions of this work. This seems to be confirmed by its textual closeness to the Gouda versions.

With this Lantslot, the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library has a rare gem in its collection. Leaving aside Van Ghemen’s prints, only five other known editions of this literary masterpiece date back to the early sixteenth century and none is held by a Flemish institution. It doesn’t happen often that unrecorded medieval or early modern editions of canonical Dutch literary works come to light. As such, for a library that prides itself on its Dutch literary heritage collection, Lantslot ende Sandryen is something to be treasured.

Jorn Hubo

jorn@vlaamse-erfgoedbibliotheken.be

Further Reading

- Beckers, Jo. “Enkele opmerkingen bij Een seer ghenoechlike ende amoroeze historie vanden eedelen Lantsloet ende die scone Sandrijn (± 1486). Van hoofse toneeltekst naar leestekst voor burgers?” in Literatuur 6 (1989), p. 222-228.

- Salemans, Benedictus Johannes Paulus. Building Stemmas with the Computer in a Cladistic, Neo-Lachmannian Way. The Case of Fourteen Text Versions of Lanseloet van Denemerken. 2000. Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen. PhD dissertation.

- Koch, Anton C-F., “Jacob van Breda” in Post-incunabula and their publishers in the Low Countries: a selection based on Wouter Nijhoff's L'art typographique, Hendrik D.L. Vervliet (ed.), The Hague : Martinus Nijhoff, 1979, p. 120-122.